Socio-Technical Seeing

Modeling The Dynamics Of Code And Attention

In conversations about software development, I often ask people whether they’ve heard of Conway’s Law. It’s a doorway to a richer conversation. We can talk about the dynamics of design — how our environment affects us as designers and how the things that we design become part of that environment in a broad feedback loop. Without this perspective, there’s so much that is puzzling about software development. Often things don’t go as planned. We blame people and processes because we miss the interplay between them and the artifacts we use and produce.

Before going forward with this line of thought, I have to stop and mention that I’m not talking about Conway’s Law by itself. Conway’s Law describes how team structure influences software structure. But, software structure can influence team structure also. There's a bidirectional feedback loop between people and code — a relationship. In a very real sense, software design is about tending this relationship.

Let’s look at a hypothetical scenario — one that shows the interplay of structure across software and teams.

Imagine that we have three teams working on separate products. Over time, each of the teams independently realizes that workflow management is a large part of their product. None of the off-the-self or open source workflow management solutions that they’ve investigated seem to be a good fit, so each team builds its own ad hoc solution.

Eventually, the developers realize that they are duplicating effort. They hold a meeting to decide how to proceed and they agree that one team’s approach is better than the others. The developers behind that approach volunteer to generalize it for use by the other teams.

It seems that this should be a happily ever after story, but almost immediately the plan is sidetracked by a new initiative. A customer needs features that impact all three of the products. The teams still have their workflow management problem, so they take the best solution and put it in a common repository as a separate project — the beginnings of a common workflow framework.

The code in the repository isn’t well-refined. It's object-oriented and it centers around a class that is meant to be the base class for a wide variety of workflows. Each team modifies that base class in different ways, and it becomes hard to read and understand.

As I write this, I can imagine what your reaction might be. You are probably saying to yourself:

Oh, no! If only they’d used <insert technology or practice here> they wouldn't have had this problem.

Many conversations about software development are like this. People want to point to the One Magic Thing™ that would’ve made a difference. If it isn’t a different technology or practice, it is something more general: better culture, different skills, or a new process.

Debating these causes and remedies can be an endless game. But, what if we step back for a second and just think about the forces involved?

Some diagrams may help.

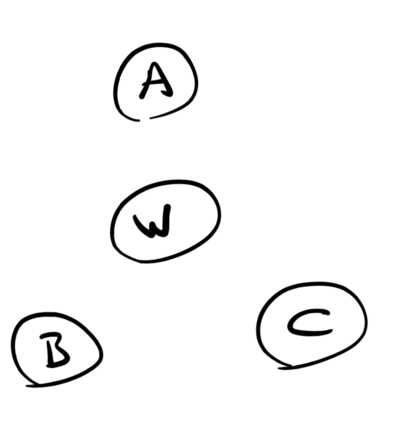

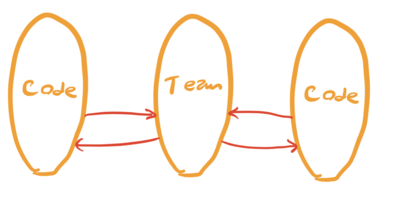

These are the teams and the common workflow management code.

I’m using circles as symbols to represent the amalgam of code and team - the code/team unit. Each of the three teams (A, B, and C) have code but the circle in the center W is more code than people; there isn’t much of a team associated with it.

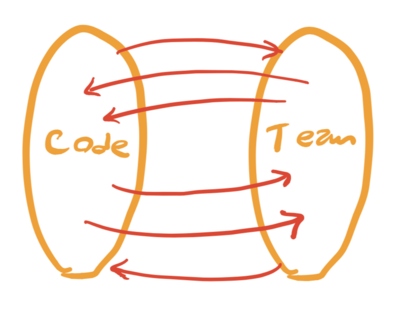

I see teams and code as the same thing, in a way. At a high level of abstraction, they are a unified entity. Code and people coexist and affect each other.

In a healthy unit, there’s no real barrier to communication between the team and its code. The code is a reflection of the understanding of the team, and the team adapts itself to the growing understanding that is rendered in the code.

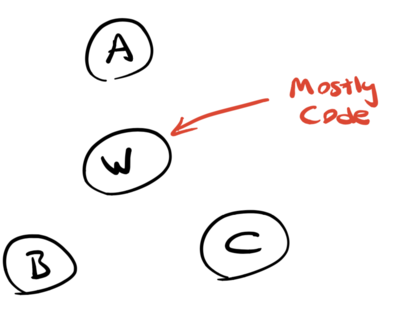

In our scenario, though, there is a problem. The circle in the center is mostly code.

It has become a place where people put code rather than a place where code is tended and cared for.

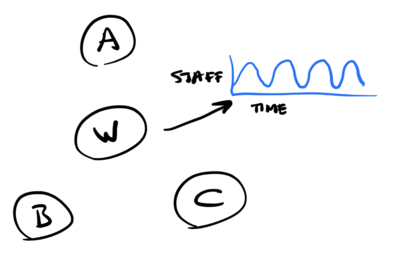

Let’s carry the story further. The teams notice that lack of staffing is a big part of the problem, so they adopt a model where one or two developers per sprint dedicate time to the workflow management framework, enhancing it themselves and reviewing PRs.

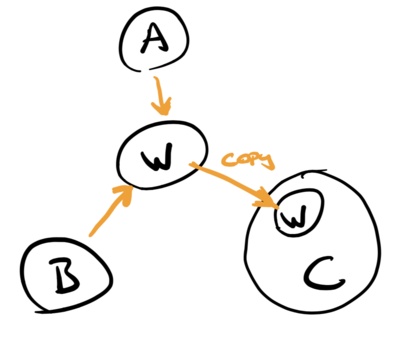

Quality improves, but eventually two of the teams decide that they would like a plugin architecture for workflow. They each volunteer a developer to work on it until the architecture is sorted out. In contrast, the third team makes the case that the plugin approach would be too much for their use case, so they just copy the code into their repository so that they can have their own version.

This is a simple scenario and most of us have probably seen similar things play out in our organizations.

I want to call attention to the diagrams, though.. the circles and lines and the story this series of pictures tells.

It seems that all of the "motion" comes from the fact that the workflow framework circle is imbalanced in the beginning. It is is all code and no team. The code is there, but it never really had consistent attention throughout our scenario.

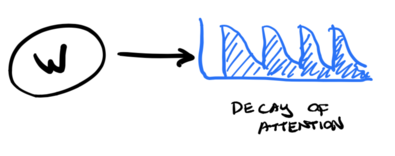

This might not seem like a problem. In open source, for instance, there are many projects that are essentially stable. They are “done” from a user’s point of view. Users don’t care whether they are under active development unless they encounter problems. But, in systems under active development, people and code form a unit and the balance between them is important. Code that exists without attention grows stale, in a way. Without continuity of knowledge and consistent activity, the things that are learned about the system fade. They have to be relearned.

Let’s look inside our circles. There are many dualities in the world. Some are very stable in the sense that each part of the dual feeds the relationship. Code and team act like that. It’s easy to see code as a passive entity but, if you are changing code you are reacting to it - its structure and meaning - as much as it reacts to you. That activity is generative. It makes the code/team system alive in a way.

When people have divided attention, work suffers. The area of code that you work for months is something that you understand deeply. The framework, off to the side, that you update just to facilitate your work may not seem as important. This is a function of distance: cognitive, temporal, and locational distance. In a way, these are all the same.

It shouldn’t be surprising to us that the workflow unit has quality problems relative to the other units. In fact, the cascade of events in the scenario seem to have all been side effects of the system’s disposition - the imbalance in the in the workflow unit. It lead to effects we can see in the code (the patchy base class), in team structure (the formation of an ad hoc team), and eventually, reuse asymmetry. Code decisions and team decisions mingle in interesting ways in development.

It’s tempting to reduce all of this understanding to a simple rule: code should have enough of a dedicated team to prevent dissolution of knowledge when it is under active development. But I that's too simple. It's good to linger in the descriptive realm a bit — see the system as it is before trying to fix it.

There are many different kinds of organizational and process scaffolding that we can introduce to try to compensate for the imbalance of team and attention. Sometimes they work, but the first step is to see the forces at play in development. The ones I’ve shown in this scenario are a few basic ones concerting attention, change and system health, but there are many more. It can be useful to diagram them in this loose way.. create models that help us think about attention, cognitive distance, knowledge dissolution and other things.

It would be easy to get into a discussion about how real these effects and forces are, but they are mental models.. sense-making that we can use to frame decisions. Personally, I think that they are as real as Conway’s Law. It took years for empirical evidence of Conway’s Law to accumulate, and perhaps the same thing will happen with some of them. I just notice, through, that very experienced developers often center around the same intuitions about design forces in software and organizations. They are things we can learn to see and factor into our decision-making.